Making Sense of Test and Measurement Protocols

- Introduction

- An Overview of the Test and Measurement Equipment Protocol Stack

- LAN - VXI-11

- LAN - TCP/IP Raw Sockets

- LAN - Telnet

- LAN - HiSLIP

- LAN - VICP

- LAN - LXI Oversees LAN Instrumentation Standards

- USB - USBTMC

- USB - Serial

- GPIB / IEEE-488

- VISA - One API that Rules Them All

- SCPI - The ‘Universal’ Command Language

- The Forgotten MATE-CIIL Command Language

- To Be Continued…

- References

Introduction

With the whole shelter in place going on, I’ve been spending a lot of time in my garage, now serving as my work office and lab. And that includes quality time with my oscilloscope, a Siglent SDS2304X.

One feature that I have used quite a bit is the ability to take screenshots to add illustrations to some of my blog posts. But I’ve always done this the primitive way by saving the screenshot on a USB drive that’s plugged into the USB type A connector on the front of the scope.

![]()

The problem with that is that you can end up with a USB drive full of screenshot bitmap files that are sequentially numbered without any futher annotation or context. It’d be much easier if I could immediately save the screenshot from the scope straight onto my computer and give them a clarifying filename.

I knew that the Ethernet and USB type B connectors on the back could be used to remote control the scope, but I had never tried.

And thus starteth my descent into the world of protocols to control test equipment.

I first start by looking at the general parts of the whole protocol stack. In later blog posts, things will get more specific.

An Overview of the Test and Measurement Equipment Protocol Stack

When you’ve never dealt with these kind of protocols before, it’s easy to get overwhelmed with all kinds of protocols, protocol layers, and APIs. It took me a while to see the forest through the trees, but here’s what I ended up with:

There are essentially 3 layers. They probably have an official name, but I’ve named them myself as follows.

-

physical layer

The physical method by which the scope is connected to your computer. Today, the 2 most common interfaces are Ethernet and USB, but older ones include GPIB (IEEE-488.1), RS-232, RS-422, and VXI bus.

-

transport layer

This is the higher level protocol that is used on top of the physical layer. When using USB, this layer is almost always the USB Test and Measurement Class (USBTMC). For Ethernet, telnet, raw sockets or VXI-11 are commonly used. Some devices support the more modern High Speed LAN Instrument Protocol (HiSLIP).

In some cases, a name will cover the physical layer and the transport layer. For example, the GPIB/IEEE 488.1 nomenclature is used for both the physical layer and the transport layer.

-

command layer

This specifies the syntax of commands that are issued over the transport layer. Most modern equipment supports SCPI, short for Standard Commands for Programmable Instruments, aka ‘Skippy’.

While SCPI is a standard at the lowest level, each brand has its own variant with it comes to commands and how they are formatted.

If this sounds all simple enough, it’s not as clear-cut as I’m making it out to be. For example, USBTMC has a messaging system that has been borrowed almost entirely from GPIB/IEEE-488.

To make things even more fun, the fact that these standards are well defined doesn’t mean that equipment follows them. Rigol oscilloscopes are known to use a different TCP/IP port number than those mandated by the standard. USBTMC has seen very buggy implementations. Some Siglent oscilloscopes support raw TCP/IP sockets as transport layer while others only support VXI-11.

When tying all of this together in an automation setup, there’s a lot of complexity to manage. But fear not: other standards were created to bring some uniformity to the whole deal. The Lan eXtensions for Instrumentation (LXI) consortium oversees standards that are related to LAN/Ethernet communication, and the Virtual Instrument Software Architecture (VISA) tries to abstract all these transport methods behind one API.

LAN - VXI-11

VXI-11 dates all the way back to 1995. It is layered on top of the ONC Remote Procedure Call (RPC) protocol, which itself is layered on top of TCP/IP. You can find the VXI-11 Specification here.

RPC is synchronous by nature, which means that a request needs to be completed before the next one can be issued. (This can be a performance bottleneck when there’s a sequence of many small calls, which is why HiSLIP was developed as an alternative.)

One interesting feature of VXI-11 is the ability to discover connected devices on the network: instead of explicitly specifying the IP address or hostname of your device, devices make themselves know by responding to a broadcast transmission.

While it’s supposed to be supported, I have not been able to to make this work with my scope!

Everything that follows in this section is nicely hidden behind APIs, but it took me a long time to figure this all out, so I’m recording it here for posterity. Feel free to skip.

Under the hood, making a connection to a VXI-11 enabled device goes in two phases:

-

RPC PortMap call to request TCP/IP communication port - Port 111

All TCP/IP connections go over ports. There is no standard port assigned for VXI-11 transactions, but RPC enabled servers often (always?) run a PortMap service on port 111.

When a client wants to establish an RPC connection, the client first issues a request to the PortMap port to ask which TCP/IP port should be used for a particular RPC service. Each RPC service is assigned a so-called program number. The program number of the VXI-11 core channel is 395183 / 0x607af. (There’s also a VXI-11 Abort Channel and a VXI-11 Interrupt channel, which have program numbers 395184 and 395185 resp.) (Section B.6 of the VXI-11 spec.)

The PortMap server replies with the port number that should be used for the actual VXI-11 RPC transaction.

In my case, the port number returned by the PortMap call is 9009. This seems to be a number that’s commonly used by Siglent scopes.

-

Actual VXI-11 transactions over the assigned port - Port 9009

Like all RPC programs, the VXI-11 RPC calls are specified in RPCL (Remote Procedure Call Language), a formal description that can be used for code generators such as RPCGEN to automatically create client and server stubs for implementation. (Section C of the VXI-11 spec.)

Wireshark was really useful to dump all the traffic between my PC and the scope, and it has built-in support for VXI-11 RPC calls!

Various documentation, code, references:

- VXI-11 Specific

- Discussion about an RPC VXI-11 call with C code

- VXI11 Ethernet Protocol for Linux

- Code also on GitHub

- Lots of VXI-11 information here, but not about portmap

- VXI-11 RPC Programming Guide for the 8065 - An Introduction to RPC Programming

-

This implements a VXI-11 server instead of a client.

The goal is to fake a Siglent waveform generator.

- Generic RCP and portmap info:

LAN - TCP/IP Raw Sockets

Instead of using VXI-11 (which is a layer on top of TCP/IP sockets), some equipment doesn’t bother and simply transmits and receives commands and data using raw sockets.

VXI-11 offers additional features such as abort and interrupt channels, but more often than not, this is not needed.

One benefit of raw sockets is that you’re not constrained by the synchronous nature of RPC calls: if you like, you can issue multiple request before fetching the data.

LAN - Telnet

Telnet is a relatively thin layer over raw sockets: it’s totally possible (and common) to telnet into a server

which supports regular sockets and type the command that would otherwise be entered by a client.

As a result, it’s not clear to me whether there’s a real difference in service on an instrument that announces raw sockets versus one that has telnet support over Ethernet.

LAN - HiSLIP

Defined by the Interchangable Virtual Instruments (IVI) Foundation (which also manages the VISA API and the SCPI specifications), the High Speed LAN Instrument Protocol is a modern and faster alternative for VXI-11.

Its primary benefit is the asynchronous ‘overlap mode’, which allows multiple commands to be transmitted without first waiting for their return data. This makes it possible to fully use the bandwidth of the Ethernet channel.

The official specification is here.

Oscilloscopes like the gently priced Keysight DSOZ204A, $305k and up(!!!), have HiSLIP support, but there must be cheaper ones too.

LAN - VICP

The Versatile Instrument Control Protocol (VICP) is another transport protocol on top of TCP/IP. It’s specific to LeCroy. While it’s still supported on many modern LeCroy oscilloscopes, most of them also support VXI-11.

I couldn’t find a real VICP specification, but you can find an open source support library, published by LeCroy engineers, on SourceForge.

References:

LAN - LXI Oversees LAN Instrumentation Standards

The Lan eXtensions for Instrumentation (LXI) consortium oversees a number of standards related to communication protocols for instrumentation and data acquisition that use Ethernet.

The list of standards can be found here and includes the LXI Device Specification, HiSLIP, Clock Synchronization etc.

USB - USBTMC

In the USB world, there are the base USB specifications which detail everything from the mechanical properties of connectors to overall protocol used to exchange data. And then there are numerous additional class specifications that describe how devices of a certain class are supposed to exchange data with a host.

The USB Test and Measurement Class Specification is the device class for, well, test and measurement equipment. The specification document is a suprisingly short 40 pages and more or less readable.

It defines a number of endpoints (virtual data channels) that must be used to transmit and receive data, message types, packet headers, and how data needs to be encapsulated inside those packets.

There is also a subclass specification that defines the communication of IEEE-488 traffic over USB.

Almost all modern test and measurement equipment today has a USBTMC compatible USB port.

USB - Serial

Some devices support the serial-over-USB protocol. These are often cheaper devices that just need a few simple ways to configure themselves.

GPIB / IEEE-488

Going back all the way to the late 1960s, there was a time when all T&M equipment had a GPIB interface.

Standarized as IEEE-488, it supports an 8-bit parallel bus that can transfer at speeds of up 8MByte/s (1MByte/s on older devices), up to 15 devices in a daisy-chained cable configuration, separation of control and data transfers (a controller can instruct one device to send data directly to multiple listening devices without being involved in the data transfer itself), device service requests (interrupts) using serial or parallel polling, etc.

There are 2 parts to the specification: IEEE-488.1 deals with the phyisical aspects and electrical signalling while IEEE-488.2 defines the command structure. The more recent SCPI standard (see below) is layered on top of the IEEE-488.2 specification.

One of the major factors behind its demise were the cost of the GPIB connector itself and the cable.

Modern equipment has dropped the GPIB connector for LAN and USB ports, but you can still find plenty of GPIB equipment in the lab. A kick-ass power supply or 6-digit multimeter from 30 years ago is very likely still a kick-ass power supply or multimeter today! And that’s reflected in their prices on eBay.

If you want to control a GPIB-equiped device today, there are USB interface dongles such as the National Instruments GPIB-USB-HS or the Agilent 82357B. One eBay, they can be found for prices of $70 and up.

The official IEEE-488 specifications are only available behind a paywall. Getting your hands on it will depends on your wallet or on your persistence in going through Google search results for the term “ieee standard digital interface for programmable instrumentation”.

Resources:

-

The first half of this 1988 video is suprisingly instructive!

-

A pretty comprehesive article that covers low level signalling protocol, connector pinout, addressing, and more.

-

Lists various command IEEE-488.2 commands, with examples on how to use them.

VISA - One API that Rules Them All

With all these different transport standards, you’d think it’ll be a nightmare to remote control various instruments, but you’d be wrong (to a certain extent…)

The IVI Foundation has the VISA API specification: an generic API that hides the lower level details of each transport protocol.

There are commercial and open source implementation for different operating systems.

NI VISA by National Instruments is one such commercial implementation. PyVISA is probably the most common open source one.

To give an idea about how easy it is to connect to my Siglent scope with PyVISA, the following code queries and prints the scope identification string over VXI-11:

import pyvisa

rm = pyvisa.ResourceManager()

siglent = rm.open_resource("TCPIP::192.168.1.177")

print(siglent.query('*IDN?'))

And this code does the same using USBTMC:

import pyvisa

rm = pyvisa.ResourceManager()

siglent = rm.open_resource("USB0::0xF4EC::0xEE3A7:SDS2Xxxxxxxxxx")

print(siglent.query('*IDN?'))

All it took was changing the resource path… Accessing a device over GPIB wouldn’t be any more complicated.

Strictly speaking, PyVISA-py is the library that implements the Python VISA backends, while PyVISA is a

utility library on top of that. In addition to PyVISA-py, PyVISA can also use the NI VISA or other

backends. On my Ubuntu Linux system, I installed the libraries by running:

pip3 install pyvisa pyvisa-py

though depending on your preference, you could also use

sudo apt install python3-pyvisa python3-pyvisa-py

SCPI - The ‘Universal’ Command Language

After going through all these transport layers, it finally time to go up one level in the stack.

The Standard Commands for Programmable Instruments (SCPI) standard is a specification from 1999 that’s layered on top of the IEEE-488.2 command specification. It can be downloaded here.

Let’s to go straight to the source to see what SCPI is trying to achieve:

Standard Commands for Programmable Instruments (SCPI) is the new instrument command language for controlling instruments that goes beyond IEEE 488.2 to address a wide variety of instrument functions in a standard manner. SCPI promotes consistency, from the remote programming standpoint, between instruments of the same class and between instruments with the same functional capability. For a given measurement function such as frequency or voltage, SCPI defines the specific command set that is available for that function. Thus, two oscilloscopes made by different manufacturers could be used to make frequency measurements in the same way. It is also possible for a SCPI counter to make a frequency measurement using the same commands as an oscilloscope.

It’s questionable whether or not SCPI achieved that goal.

To fetch an acquired waveform from an oscilloscope, SCPI defines the DATA(CURVe(..)) command.

My Tektronix TDS 420A, has the

CURVe?

command (no DATA(...)) required, my Siglent uses WF?, a Rigol scope uses WAV:DATA?,

and Rohde-Schwartz has :DATA?.

The only consistency here is that there is none.

In practise, every kind of instrumentation equipment will need a vendor or even device specific driver for remote control…

The Forgotten MATE-CIIL Command Language

This section was added in December 2022.

I was recently looking at adding a pymeasure driver

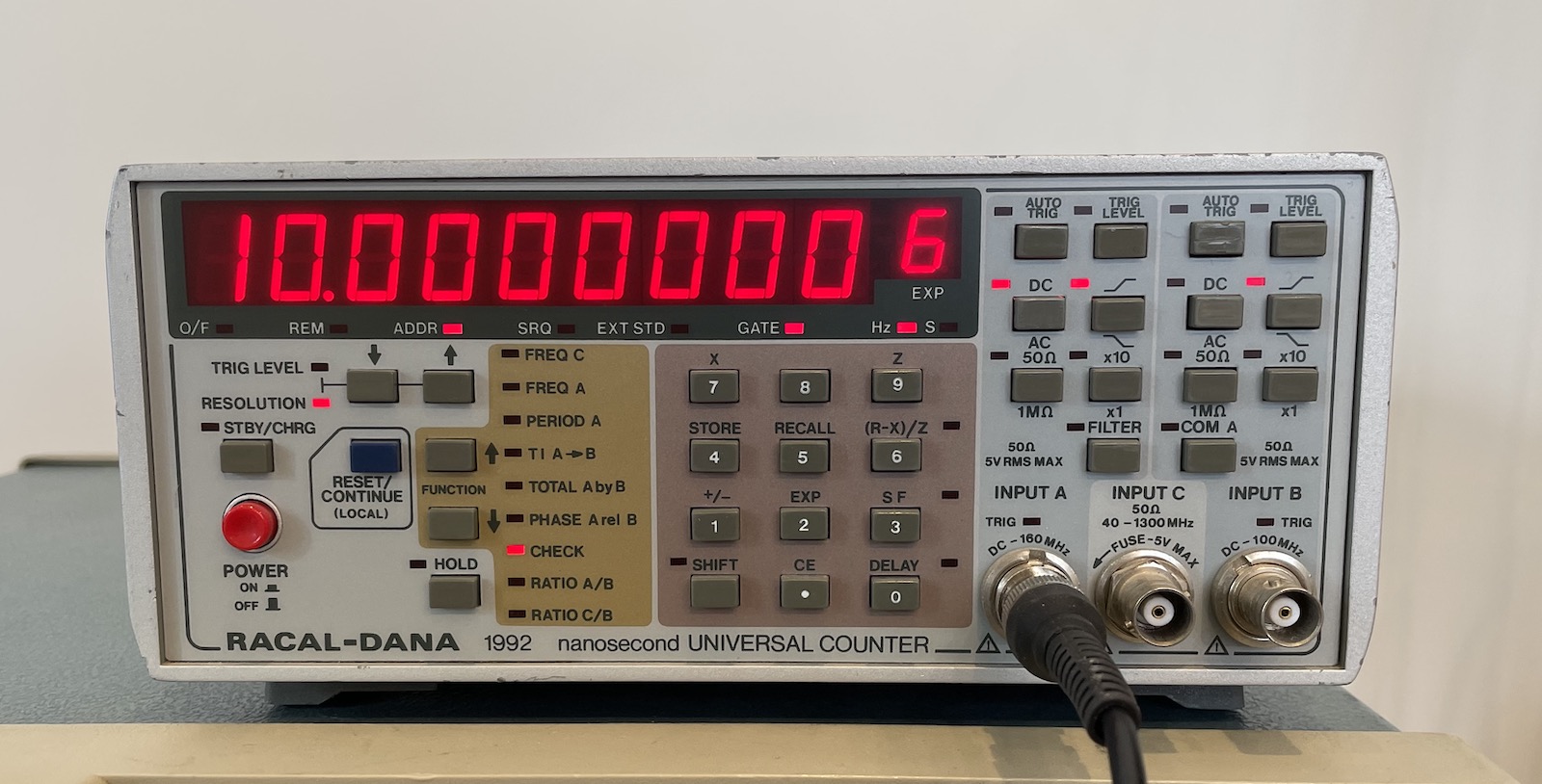

for my Racal-Dana 1992 universal counter with GPIB interface.

It took me a couple of hours of not getting anywhere at all before I found out my unit has a GPIB plug-in card with a jumper that selects between the advertised GPIB commands from the manual, and an entirely different command set that’s called MATE-CIIL. MATE and CIIL are acronyms for Modular Automated Test Equipment and Control Interface Intermediate Language.

Google doesn’t turn up a lot of information, but Project MATE was an initiative of the US Air Force to convert CIIL with Test Module Adapter (TMA) into the device-specific, non-standard commands of existing equipement. There’s supposed to a MATE STD 2806763 specification that defines the CIIL commands for different types of instruments, but once again, Google doesn’t get me any futher other than confirming its existence.

In the early 1990ies, HP came up with TML, Test Measurement Language, which was eventually made license-free and renamed as… SCPI.

Like my Racal-Dana, you can find some equipment from the mid to late eighties that supports MATE/CIIL natively, without the need for an external TMA box, but all of that is now just a distant memory.

To Be Continued…

So far, everything covered here is only describes what’s out there and how it all plays with eachother.

The next step is to show how all of this can be made to work, the pitfalls etc.

That’s for upcoming blog posts…